Promethium 61

Uses and properties

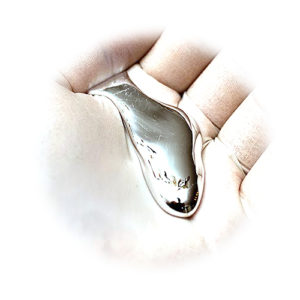

Image explanation

The image is based on a scene from an Ancient Greek vase. It depicts the god Atlas witnessing Zeus’ punishment of Prometheus. Prometheus was chained to a rock on a mountain top. Every day an eagle tore at his body and ate his liver, and every night the liver grew back. Because Prometheus was immortal, he could not die, but he suffered endlessly.

Appearance

A radioactive metal.

Uses

Most promethium is used only in research. A little promethium is used in specialised atomic batteries. These are roughly the size of a drawing pin and are used for pacemakers, guided missiles and radios. The radioactive decay of promethium is used to make a phosphor give off light and this light is converted into electricity by a solar cell.

Promethium can also be used as a source of x-rays and radioactivity in measuring instruments.

Biological role

Promethium has no known biological role.

Natural abundance

Promethium’s longest-lived isotope has a half-life of only 18 years. For this reason it is not found naturally on Earth. It has been found that a star in the Andromeda galaxy is manufacturing promethium, but it is not known how.

Promethium can be produced by irradiating neodymium and praseodymium with neutrons, deuterons and alpha particles. It can also be prepared by ion exchange of nuclear reactor fuel processing wastes.

| Group | Lanthanides | Melting point | 1042°C, 1908°F, 1315 K |

| Period | 6 | Boiling point | 3000°C, 5432°F, 3273 K |

| Block | f | Density (g cm−3) | 7.26 |

| Atomic number | 61 | Relative atomic mass | [145] |

| State at 20°C | Solid | Key isotopes | 145Pm, 147Pm |

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f56s2 | CAS number | 7440-12-2 |

transcript :Chemistry in its element: promethium

(Promo)You’re listening to Chemistry in its element brought to you by Chemistry World, the magazine of the Royal Society of Chemistry.

(End promo)Meera Senthilingam

This week, we enter the world of Greek mythology to reveal the great powers of the element promethium.

Brian Clegg

Of all the figures in Greek myth, Prometheus has to be one of the most significant for science. This Titan brought fire to mankind. For that gift he was punished by having his liver pecked out by an eagle every day. Such was the reward for being an early technologist.

In other legends Prometheus gave us maths and science, agriculture and medicine – or even created humans in the first place. This uncertainty of just what Prometheus was responsible for is echoed in the uncertainty of who discovered the element promethium, number 61 in the periodic table.

As far back as 1902 there were suspicions that such an element should exist. Promethium sits in the lanthanides, the floating bar of elements that squeezes between barium and lutetium. The rare earth elements either side of it, neodymium and samarium, seemed not to have the right relationship in their chemical properties to be neighbours. It was as if there were a gap between, and Czech chemist John Bohuslav Branner suspected that a missing element occupied that gap.

One of the reasons promethium was so elusive for a relatively low atomic number element is that it doesn’t have a stable state – it’s one of only two elements below 83 that only has radioactive isotopes, the other being technetium. The most stable form of promethium has a half life of just 17.7 years – that’s promethium 145 – so it’s hardly surprising that it proved difficult to pin down, though it does occur naturally in tiny quantities in the ore pitchblende when uranium 238 splits spontaneously. The amounts produced are so small – around a trillionth of a gram from a tonne of ore – that promethium was unlikely to be discovered this way. However it would be wrong to say that promethium is negligible in nature. It has been detected using spectroscopes, devices that analyze materials from the light they give off, on the star HR465 in the constellation Andromeda. No one is quite sure why this star is pumping out what must be considerable quantities of promethium.

This grey metallic element gives off beta particles – electrons from the nucleus – as it decays. These can cause radioactive damage in their own right, but prometheum is probably most dangerous because those beta particles generate X-rays when they hit heavy nuclei, making a sample of promethium bathe its surroundings in a constant low dosage X-ray beam.

It was initially used to replace radium in luminous dials when it was realized that radium was too dangerous. Promethium chloride was mixed with phosphors that glow yellowy-green or blue when radiation hits them. However, as the dangers of the element’s radioactive properties became apparent, this too was dropped from the domestic glow-in-the-dark market, only used now in specialist applications.

The obvious use of promethium is for portable X-ray devices, though this isn’t an application that has been properly developed yet. Instead the element’s beta radiation has been used in industry to measure the thickness of materials, and the isotope promethium 147 has been used in nuclear batteries. These are long life power sources that make use of the beta radiation (which is, after all, made up of electrons, the source of an electrical current) to generate power. Such batteries, often less than a centimetre across, can keep in action for around five years, twice promethium 147’s half life. They have been used in everything from missiles to pacemakers.

In its early days, nuclear power seemed to promise vast amounts of cheap, portable energy. Science fiction of the period featured walnut-sized generators that could run a household, all driven by nuclear fission. In nuclear batteries, promethium comes about as close as we’ve ever got to a portable nuclear powered energy source. So in that small way at least, it lives up to the titan it was named after – Prometheus, the bringer of fire.

Meera Senthilingam

So a provider of portable and long life power named after the bringer of fire. That was science writer Brian Clegg bringing us the powerful and mythological chemistry of promethium. Now next week an element that shoots us off into outer space, quite literally.