Gallium price 4N 5N 6N gallium metal

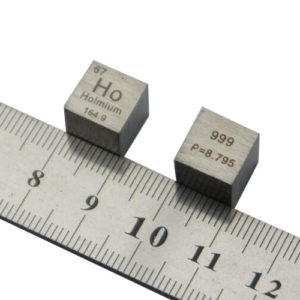

| Product Name | High Purity Gallium |

| Standard | GB/T1475-2005 (Ga4N) |

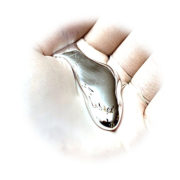

| Appearance | silver white solid |

| Molecular Formula | Ga |

| Atomic Weight | 69.72 |

| Melting Point | 29.76°C |

| Boiling Point | 2403°C |

| Density | 5.904g/cm3 |

| electronegativity | 1.6 |

| CAS No. | 7440-55-3 |

| EINECS No. | 231-163-8 |

Uses and properties

The image reflects on puns relating to the origin of the element’s name. Lecoq de Boisbaudran named the element after France (‘Gaul’ in Latin) and also himself, since Lecoq, which means ‘the rooster’ translates to ‘Gallus’ in Latin. A silvery metallic rooster is shown on a background of an antique map of France.Appearance Gallium is a soft, silvery-white metal, similar to aluminium.

Uses

Gallium arsenide has a similar structure to silicon and is a useful silicon substitute for the electronics industry. It is an important component of many semiconductors. It is also used in red LEDs (light emitting diodes) because of its ability to convert electricity to light. Solar panels on the Mars Exploration Rover contained gallium arsenide.

Gallium nitride is also a semiconductor. It has particular properties that make it very versatile. It has important uses in Blu-ray technology, mobile phones, blue and green LEDs and pressure sensors for touch switches.Gallium readily alloys with most metals. It is particularly used in low-melting alloys.It has a high boiling point, which makes it ideal for recording temperatures that would vaporise a thermometer.Biological roleGallium has no known biological role. It is non-toxic.

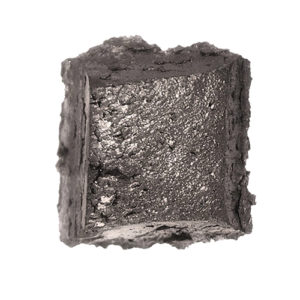

Natural abundance

It is present in trace amounts in the minerals diaspore, sphalerite, germanite, bauxite and coal. It is mainly produced as a by-product of zinc refining.The metal can be obtained by electrolysis of a solution of gallium(III) hydroxide in potassium hydroxide.

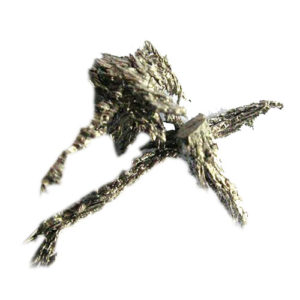

Gallium, you see, melts at 30oC, which means that on a hot day, you hold it in your pocket at your peril. Surprisingly however it’s not very volatile. In fact Gallium has the largest liquid range of any material known to man. Its boiling point is just over 2400oC. So unlike other liquid metals, there is no toxic vapour to worry about. Bizarrely as well, the metal contracts as it melts, rather like water. So solid Gallium floats on its liquid, a property shared only by a couple of other elements, Bismuth and Antimony. The reason for this weird melting behaviour has been a matter of argument and speculation for about 50 years. It’s now fairly well established that Gallium surrounds itself with more of its neighbours when in the liquid than in the solid, although the reasons for this still remains obscure.

Yet for all its strangeness the discovery of this odd element was no accident. Dmitri Mendeleev, the bearded Russian chemist who constructed the periodic table as we know it today, spotted a number of gaps and discrepancies in his arrangement. One of these was the absence of an element which he expected to fit below Aluminum. So confident was he in the correctness of his framework that he named the as yet undiscovered element ekaaluminium. Six years later in 1875, an ambitious French element hunter François Lecoq de Boisbaudran one of the earliest proponents of the new-fangled technique of spectroscopy spotted a line in the violet part of the visible spectrum at 417nm in a sample of zinc sulphide, he realized that this must come from a new element. Working in his home laboratory in spite of starting from some 52 kilos of an ore from the Pyrenees, it took three weeks for him to accumulate a couple of milligrams of the mysterious material. He then scaled up his extraction and took the product of his labours to Paris where he studied it further in Adolphe Wurtz’s lab. Just before Christmas in 1875, Lecoq presented his results to the French academy proudly displaying a sample of almost 600mg, less than a gram of material harvested from 450 kilos of ore. And the name Lecoq patriotically chose to base it on the Latin name for France, Gallia; Gaul in English. But it was immediately pointed out that there might be something more to the name than met the eye. The Latin word for a rooster is Gallus, Lecoq, rooster, Gallium, get it. It seems he may have been a rather cunning linguist as well as a chemist. Either way, Lecoq could look back with some satisfaction at having helped to cement Mendeleev’s table, was the foundation stone of chemistry. He then moved on to the intriguing mystery of the ‘rare earths’, ultimately isolating two more elements and conforming the existence of several more.

Gallium soon moved into the main stream of chemistry. Nowadays the metal itself finds few uses, but its compound with arsenic, gallium arsenide has for several years been touted as a possible replacement for Silicon. Since not only is it a semiconductor but it is one with a direct band gap, in other words it can be made to emit light, a property which is particularly useful for infrared but also visible LEDs. Gallium arsenide solar cells are also much more efficient than those made of conventional Silicon and are being used in solar powered cars and in space probes.